Today

we take the daily weather reports for granted and easily forget that

just at the beginning of the 19th century, during Goethe's lifetime,

one would never so much as have thought of a weather forecast based

on science. Not even the atmospheric variables permitting such a forecast

were known. It was just empiricism such as the knowledge of peasants,

shepherds and sailors that was available. Against this background the

cloud classification of Luke HOWARD (1772 -1864) shows its real importance.

With his work, "On the Modification of Clouds", this pharmacist

and apothecery from London, in 1803, laid the cornerstone for a classification

of clouds that, in its fundamental outlines, is still valid today. If

we speak of Goethe's meteorological observations we have to speak of

Luke Howard because it was he who coined Goethe's scientific view of

meteorology and his poetic reflections of meteorologic phenomena.

The Way

to the Poem "In Honour of Howard"

In an as simple as brilliant way Howard classified the clouds into four

basic forms according to the seperate vertical levels of the atmosphere.

Simple because these basic forms were subdivided phenomenologically; brilliant

because behind his considerations there was a sure feeling that the vertical

distribution follows certain physical laws.

Howard first

names the main cloud types: cirrus (feather cloud), cumulus (heap cloud)

and stratus (layer cloud) Furthermore, he identifies mixed type forms:

cirro cumulus, cirro stratus, cumulo stratus, and later, added cumulo

cirro stratus, also named nimbus, a rain cloud and a type of its own.

It has to be remarked, however, that his classification disregards the

mid-level clouds altocumulus and altostratus as well as the rain cloud

nimbostratus which reaches from low to mid-atmospheric levels. This, however,

does not belittle Howard's scientific achievements.

From Howard's

observations we can conclude that he attributed the different cloud types

to the different altitudes. The vertical structure of the atmosphere was

still rather unknown during his time. It was perceived from mountain climbing

that pressure and temperature decrease with height but the thermodynamic

context of pressure, temperature and humidity - and, thus, the origin

of cloud formation - was deciphered by scientists only later in the 19th

century.

Goethe correctly

recognized Howard's work as a breakthrough. It is well known that for

Goethe empiricism was the key to understanding nature. This explains his

enthusiasm for Howard's classification that, for the first time, gave

an empirically founded systematization of the clouds. Consequently, he

dedicated his poem "In Honour of Howard" (1821) to him:

"But Howard gives us with his clearer mind

The gain of lessons new to all mankind;

That which no hand can reach, no hand can clasp,

He first has gain'd, first held with mental grasp.

Defin'd the doubtful, fix'd its limit-line,

And named it fitly. - Be the honour thine!"

(The

translation of Goethe's poems follows D.F.S. Scott, 1949)

Howard's

System, Seen as Physics

Howard's vertical structural level of the clouds is based on meteorological

facts. Together with the decrease of pressure with increasing height the

atmosphere is typically characterized by a negative vertical gradient

of temperature. Up to the lower stratosphere (which in our latitude is

around 10 to 12 kilometres high) temperature decreases with height. Clouds

consist of condensed water in the form of cloud droplets or water in cristalized

form, i.e. ice. Clouds with a water/ice combination also exist.

Cloud formation takes place when the temperature drops below a certain

value (the dew point temperature). The (invisible) water vapour then condenses

onto tiny particles in the air, the condensation nuclei - a visible cloud

is formed. Howard's classification of cirrus- (feather-) clouds, cumulus-

(heap-) clouds and stratus- (layer-) clouds refers exactly to the fact

that at temperatures lower than -35 °C every cloud consists completely

of ice, at temperatures higher than 12 °C completely of liquid water

(due to reasons of cloud physics, water in the free atmosphere does not

freeze abruptly at 0 °C). His great achievement was to analyze this

without founded knowledge of the atmophere's vertical structure during

his time.

In spite

of all progress in cloud physics and regardless of all the refinements

that is included in the systematics of the World Meteorological Organization

WMO, Howard's purely empirical observations are still valid today. Still

nowadays the multitude of clouds can only be described descriptively;

and over and over again it happens that the meteorologist on duty when

doing his 3-hourly observation work detects cloud forms that can hardly

be squeezed into the narrow pattern of meteorological service routines.

Goethe

as a Meteorologist, Howard as a Poet

Goethe in, 1815 learnt to know the work of Howard when he, as the Director

of the Institute for Arts and Science in the Duchy of Saxony-Weimar, was

active in founding a meteorological station on the Ettersberg hill near

Weimar. In 1822 he got in mail correspondence with Howard.

Comparing

Luke Howard's scientific description of the main cloud types with Goethe's

poetic description, the empirically precise scientist from England and

the poet from Germany are coequal.

Example stratus: Howard names this layer cloud shortly and precisely as

"a widely extended, continuous, horizontal sheet, increasing from

below."

Stratus (Cap de Rosiers, Canada, 27.07.1991,

13:05 LST, photo: F. Ossing)

Goethe portrays

the stratus cloud very poetically:

"When o'er the silent bosom of the sea

The cold mist hangs like a stretch'd canopy;

And the moon, mingling there her shadowy beams,

A spirit, fashioning other spirits seems;

We feel, in.moments pure and bright as this,

The joy of innocence, the thrill of bliss!"

Example

cumulus: Howard sketches this cloud clearly and briefly as "convex

or conical heaps, increasing upward from a horizontal base".

Once again, the real accomplishment lies in a short, but precise definition.

Cumulus (Sonneberg/Harz, Germany, 15.06.1974,

11:00 LST, photo: F. Ossing)

Goethe subtends

this with his poetical accomplishment:

"

... High as the clouds, in pomp and power arrayed,

Enshrined in strength, in majesty displayed;

All the soul's secret thoughts it seems to move,

Beneath it trembles, while it frowns above."

Example

cirrus: Howard describes this feather cloud as "parallel,

flexuous, or diverging fibres, extensible in any or in all directions",

a short definition that still today can cope with the standards of the

World Meteorological Organization.

Cirrus (Coesfeld, Germany, 22.12.1974, 10:50

LST, photo: F. Ossing)

To Goethe

the cirrus appears in this way:

" … Then like a lamb whose silvery robes are shed,

The fleecy piles dissolved in dew drops spread;

Or gently waft to the realms of rest,

Find a sweet welcome in the Father's breast."

And finally

the example of the nimbus: here Howard's definition seems not to

be secure, this rain cloud could be a thunderstorm (cumulonimbus), a raining

cumulus cloud, or a layer cloud with precipitation: "Nimbus. The

rain cloud. A cloud or system of clouds from which rain is falling. It

is a horizontal sheet, above which the cirrus spreads, while the cumulus

enters it laterally and from beneath."

"Nimbus": does L. Howard mean nimbostratus

(Akkrum, Netherlands, 19.08.1981, 16:05 LST, photo: F. Ossing)

...

Goethe also

sees the rain falling from the nimbus but definitely refers to a thunderstorm:

"Now downwards by the world's attraction driven,

That tends to earth, which had upris'n to heaven;

Threatening in the mad thunder-cloud, as when

Fierce legions clash, and vanish from the plain; -"

...or, like Goethe, the cumulonimbus (Potsdam,

17.08.2000, 14:50 LST, photo: F. Ossing)

?

Goethe,

by the way, reproduces the atmospheric water cycle in his "In Honour

of Howard": "As clouds ascend, are folded, scatter, fall…".

The atmospheric water vapour condenses to cloud droplets (here: stratus),

in cumulus clouds these cloud droplets rise up to the freezing level and

form snow crystals from which raindrops develop that fall to the ground.

In particular in thunderstorms (cumulonimbus) the upper part of the cloud

changes into cirrus (the "anvil" of a thundercloud). This water

cycle is also mentioned in Howard's paper.

It may be

remarked here that Goethe takes on clouds and other meteorological phenomena

not only in this poem but also frequently in his complete works. As an

example we recall here the vision of Dr. Faustus who in the clouds, "formlessly

huge and towering it hangs in far icy eastern hills", fancies

to recognize Helena (Faust II).

"... towering it hangs in far icy eastern

hills ", shower cloud with icy upper part (Neustadt i.H., 27.08.78,

12:30 Uhr, photo: F. Ossing)

Meteorological

Blur: Where is the Mid-level?

Already Schöne (1969, S. 29) alludes that Goethe uses the nomenclature

of Howard as a construction kit. Wherever he finds that Howard's systemization

has to be altered Goethe develops his own termini in which his understanding

of the atmosphere condenses.

This is consequent in so far as Howard's cloud classification in fact

inhibits some blurs.

Let us reconsider the above mentioned "nimbus" cloud. We have

seen that rain may fall from a thunderstorm, a cumulus or from a nimbostratus.

These three clouds belong to different atmospheric levels: the cumulus

is part of the low clouds, nimbostratus is a mid-level cloud, and the

cumulonimbus, a thunderstorm, vertically expands through all the three

levels. Howard accordingly calls the rain cloud a "nimbus or cumulo-cirro-stratus".

This meteorological unsharpness corresponds to a linguistical unpreciseness.

Modern meteorology defines low, mid-level and high clouds based on cloud

physical reasons: while - generally spoken - low clouds consist of cloud

droplets, high clouds are a conglomeration of ice crystals. Mid-level

clouds are a mixture of cloud droplets and ice.

Luke Howard could not have been aware of this physical background, his

pioneer work was exactly that he created a cloud classification that is

valid still today without this knowledge. On the other hand, however,

this results in a distinction between mid-level and high clouds that is

only diffuse. The mid-level altostratus as an individual cloud type is

not found, and under the category "cirro-cumulus" there are

subsumized altocumuli or even stratocumuli.

Altocumuls

skyl (Bay du Vin, New Brunswick, Canada, 30.07.91, 20:05 LST, photo:

F. Ossing)

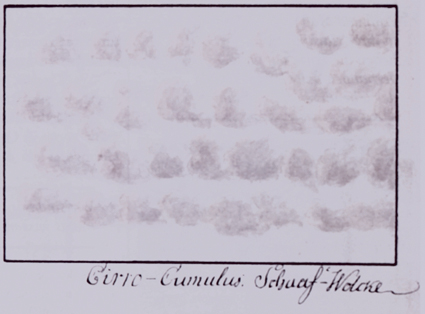

This impreciseness

is reflected in a picture of "sheep cloud" that Goethe labelled

himself as "cirro-cumulus" (Goethe-Nationalmuseum Weimar, Inv.Nr.

1533). This picture definitely shows mid-level altocumuli with shading

in the clouds body, and not cirrocumuli that do not show such a shading.

Altocumulus

clouds, named erroneously as "Cirro-Cumulus" by Gothe (1817,

pencil and Aquarell on paper, Goethe-Nationalmuseum Weimar, Inv.Nr. 1533)

What

is left:

As a Privy Council and Minister of the Duchy of Saxony-Weimar Goethe had

the arts and science under his direction. His weather theories, especially

his "Versuch einer Witterungslehre" (Attempt on a Weather Theory,

1825) today seem strange to us, when he tries to explain the weather-driving

forces of high and low pressure systems by the earth's body that breathes

the air in and out. Goethe as a theoretically erroneous theorist is opposed

by the weather practitioner Goethe. Under Goethe's supervision, starting

with the Weimar weather station that was established in 1815, a weather

observation network was installed as one of the first in Germany. The

records taken here can be understood as one of the roots of scientific

climatology and meteorology in Germany. Long before he learnt about Howard's

paper, Goethe engaged himself with the weather, drew cloud sketches and

measured temperature and pressure.

With the

acknowledgement of Howard's classification, however, an intensification

of Goethe's meteorological ideas takes place. It speaks in favour of Goethe's

self mockery when he puts himself on in a soliloquy:

"Disciple

of Howard, strangely

You look around and above you every morning

To see whether the mist falls or rises

And what clouds are showing."

- exactly, when in the morning we take a glance out of the window to see

if the weather forecast is right, "the mist falls or rises ",

before we leave the house. It may be true that nowadays and in our latitude

we no longer depend so much on weather conditions as did our ancestors

250 years ago. Yet weather is still an element of nature that touches

us directly every day.

References:

Goethe, J.W., "Schriften zur Naturwissenschaft", Reclam,

Stuttgart 1977

Luke Howard, :"On the Modification of Clouds", Original

in: Philosophical Magazine XVI, London 1803, Nachdruck in : Hellmann,

G., Neudrucke von Schriften und Karten über Meteorologie und Erdmagnetismus,

No. 3, Berlin 1894

Other Authors:

Hamblyn, R., "The Invention of Clouds: How an Amateur Meteorologist

Forged the Language of the Skies", London, Picador, 2001, pp. 256

Schöne, A., "Über Goethes Wolkenlehre", in: Jahrbuch

der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen für das Jahr 1968. Göttingen:

Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht 1969, S. 26-48

Schönwiese, C.-D., "'Ein Angehäuftes, flockig löst sich's auf'

- Goethe und die Beobachtung der Wolken", in: Forschung Frankfurt.

Wissenschaftsmagazin der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt

a.M., Nr. 2/1999, S. 12-18

Scott, D.F.S.: "Some English Correspondents of Goethe" Methuen,

London, 1949, pp. 51-54

Different contributions in:

Wehry, W. / Ossing, F., "Wolken - Malerei - Klima in Geschichte

und Gegenwart", Eigenverlag der Deutschen Meteorologischen Gesellschaft,

Berlin, 1997, 192 S. (German only)

Cloud classification:

WMO (World Meteorological Organization), "International Cloud

Atlas", Vol. II, Genf, 1987

A cloud

catalog including more than 50 photos and description is found here:

Neumann, N./ Ossing, F./ Zick, C.: "Wolken-Ge-Bilde",

("Cloud Scapes") CD-ROM, Deutsche Meteorologische Gesellschaft

1997, Berlin

Comprehensive information (in German) on Goethes work:

www.goethezeitportal.de/

Further

reading on arts and science is here:

'Arts

and Science' at GFZ.

|

![]() Franz Ossing; translation:

Mary Lavin-Zimmer, GFZ

Franz Ossing; translation:

Mary Lavin-Zimmer, GFZ